Anne Bradstreet’s “Contemplations” and New England Nature

Excerpts from my Florilegium Poetry project

“Soul of this world, this Universe’s Eye"

“Nature teacheth bees to do so when as the hive is too full, they seek abroad for new dwellings; so when the hive of the commonwealth is so full that tradesmen cannot live one by another, but eat up one another, in this case it is lawful to remove.”

—God’s Promise to His Plantation, John Cotton, 1620

When the first Puritan settlers came to New England in 1630, not much was known of the naturalistic landscape of their new home. It is commonly believed that the Puritans viewed nature as a dangerous wilderness that posed an immediate threat to their society, the natural world was not a thing of beauty but an entity to be tamed and cultivated. While this idea is deeply rooted and evident in the literary and historical works of William Bradford, Michael Wigglesworth, and Cotton Mather, it is the poetry of the Puritans in which the potential of the natural world appears in abundance. It is the work of Anne Bradstreet that illustrates how the beauty of the natural world was perceived through the eyes of a Puritan. Bradstreet, an early Puritan poet and diarist who arrived in New England in 1630, wrote in private as she raised her eight children. Bradstreet is now recognized for her expression of the struggles she faced in true acceptance of Puritan beliefs and the question of “eternal life.” Bradstreet grapples with themes of religion, earthly experience, and the dynamics of family life as a woman and as a mother. It is one of her later works: “Contemplations” written in 1645, in which the question of the afterlife collides with the experience of nature and an otherworldly love is exhibited for the Earth itself.

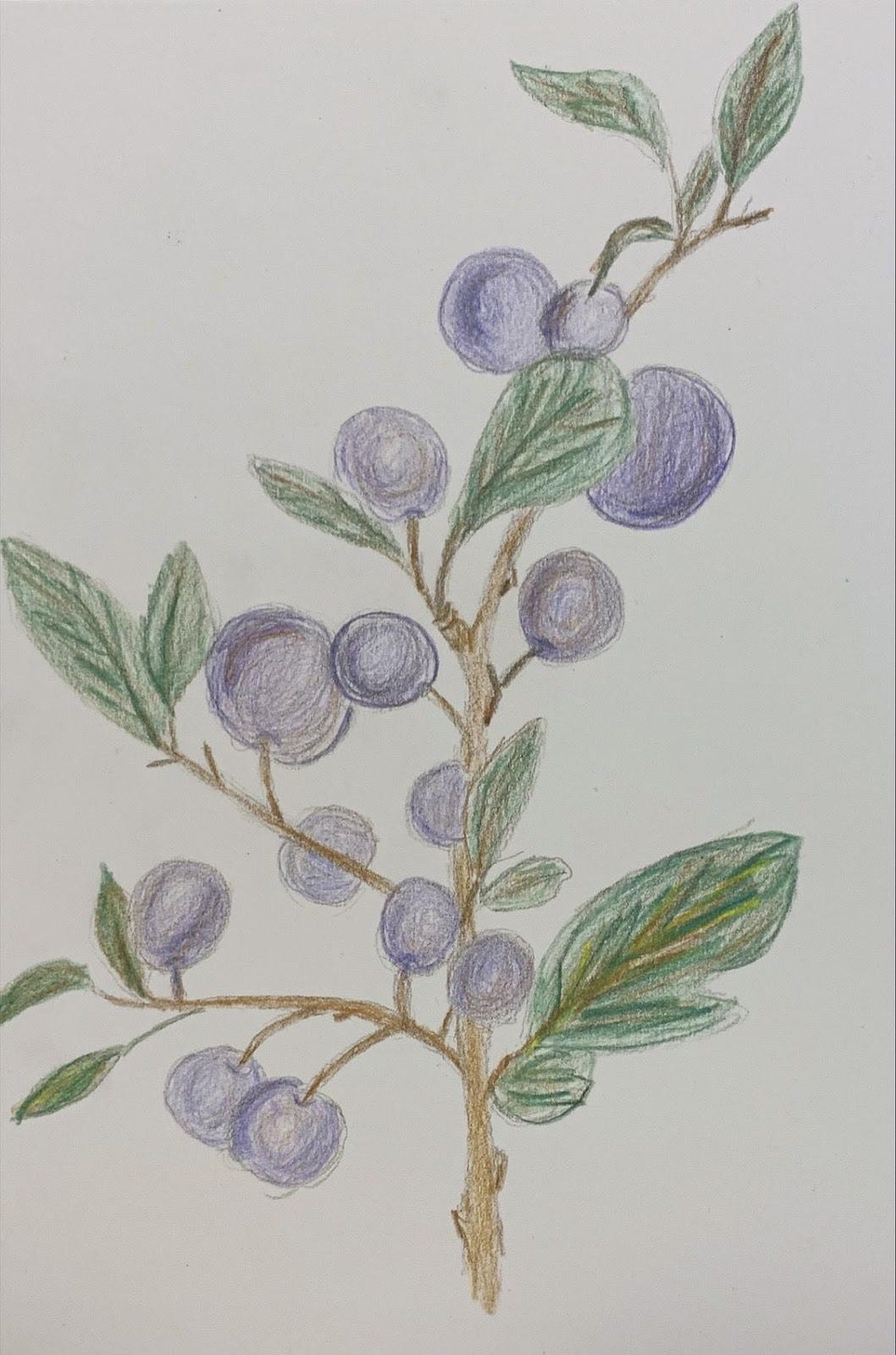

In the very first lines of “Contemplations” Bradstreet begins to paint an image of the natural world. She writes: “The trees all richly clad, yet void of pride” (Contemplation #1, Line 3), which evokes a sense of humbleness in nature. Despite the bounty of leaves that the tree has grown, the naturalistic being gleams no sense of pride from its accomplishment. The leaves to Bradstreet are an accomplishment, a creation of new life, yet to the tree they are no source of pride.

In connection with the many controversies within Puritan society, particularly as life in New England was being established, there was a shift in the understanding of what constituted wealth and what that implied about one’s status to God. Wealth was viewed as an indicator of a saved afterlife, and this theme contributed to the greed felt by the Puritans. In Bradstreet’s nature poetry, she portrays nature as lacking this human greed. She follows this with another suggestion of the modesty of nature: “their leaves and fruits seem’d painted but was true” (Contemplation #1, Line 5), which suggests that the beautiful appearance of nature is not a false face put on but instead something “true.” In Bradstreet’s characterization of nature lacking pride in its individual wealth, and deceitfulness in appearance, she appears to be contrasting nature with humans.

Further on in the poem, Bradstreet contemplates the longevity of the natural world in comparison with humans. As a Puritan woman, Bradstreet was boldly questioning the mortality of human life. She writes on observation of an Oak tree and its resilience in life throughout “hundreds” of winters: “If so, all these as nought, Eternity doth scorn” (Contemplation #3, Line 2). The ethereal life of the Oak in comparison with the brief life of humans is something Bradstreet repeatedly contemplates, as it appears as though she questions the divine nature of God, and why nature itself experiences the Earth for a much longer period of time than humans. There is a sense of God’s granting the natural world a longer life than humans for a reason, with the modesty of the natural world being a leading cause. The Oak in Bradstreet seems to represent a naturalistic heaven. Bradstreet illustrates its great height by evoking an image of the heaves, writing that the, “ruffling top the Clouds seem’d to aspire” (Contemplation 3, Line 2).

In the third contemplation, Bradstreet pauses to reflect on her own reflection. As she has been personifying the Earth, she has been moving further and further away from Puritan beliefs that God is the ultimate divine power. As she marvels at the power of the sun, she writes: “No wonder some made thee a Deity: / Had I not better known (alas) the same had I” (Contemplation #4, Lines 5-6). In this personal admittance, Bradstreet is revealing that if she was not tied down by her spiritual beliefs of Puritanism, she would have likely believed in the spiritual power of the sun, and its creation of the natural world. There is a divorce here from Christianity, a shift in Bradstreet’s suggestion of a “deity” without a direct reference to God. This comes s a stark contrast to the works of other Puritan poets, George Herbert, John Donne, the masculine God that is so deeply rooted in the history of Puritan poetry. This is an important moment in Bradstreet’s poem, as it is a declaration likely to have her dismissed from the community if it had been made public. In giving the sun a voice, and a power similar to God, Bradstreet was committing a sin.

Further along in “Contemplations,” Bradstreet reflects on her own mortality, and how she might best express her spirituality and belief in God. In comparison to the natural world and the “lifetime” of the Earth, she writes that the Earth will remain alive and bountiful, while a human “grows old, lies down, remains where once he’s laid” (Contemplation #18, line 7). In this expression of emotion, Bradstreet seems to be longing for this everlasting existence that the Earth maintains, but seems to suggest that her belief in God will provide her with a different version of this eternity. This conflicting and evolving feeling of her own religion is repeatedly connected to the differences she has observed between plants and humans. Bradstreet seems to struggle with the hope that she herself contains some capacity for an afterlife or a rebirth.

This categorization of the human experience being unequal to the everlasting existence of nature is further explored in Contemplation #19. Bradstreet writes that humans are “curs’d” (Contemplation #19, Line 2) in their short life and their inherent lack of any promise of a rebirth.

She writes that unlike plants that can regenerate and regrow from any bodily loss, humans lack that ability; “Nor youth, nor strength, nor wisdom spring again” (Contemplation #19, Line 5). The categorization of death in this way is striking when considered with the Puritan belief of predestination. One might argue that Bradstreet was questioning the legitimacy of predestination altogether in these lines. If one has no power over their fate to begin with, is there ever any value in comparison with the eternal and everlasting power of the natural world?

Imagery of nature is repeatedly used by Bradstreet as she questions not only her own individual spirituality, but the entirety of her existence as a mortal being. As one observes her intense individual connection with the world around her, it is worth questioning how widely applicable Bradstreet’s observations were to her fellow Puritans. The importance of the natural world as a creation of God was undeniably observed, but Bradstreet presents something unique in the way she categorizes the natural world. In “Contemplations,” the world of 1965 New England feels alive, and the plants growing on the Earth seem to be breathing a new life and unique spirituality into Bradstreet as a woman, as a puritan, and as a human being.

Works Consulted

Bradstreet, Anne. “Contemplations.” The Poetry Foundation. 1645. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/43699/contemplations.

Callivott, J. Baird, Ybarra, Priscilla S. “The Puritan Origins of the American Wilderness Movement.” Natural Humanities Center, July 2001. http://nationalhumanitiescenter.org/tserve/nattrans/ntwilderness/essays/puritan.htm

2. Making Nature Sacred: Literature, Religion, and Environment in America from the Puritans to Present By John Gatta,

Lane, Belden C. “Two Schools of Desire: Nature and Marriage in Seventeenth-Century Puritanism.” Church History, vol. 69, no. 2, June 2000, p. 372. EBSCOhost, doi:10.2307/3169585.

Nelson, Robert H. “Calvinism Without God: American Environmentalism as Implicit Calvinism.” Implicit Religion, vol. 17, no. 3, Sept. 2014, pp. 249–273. EBSCOhost, doi:10.1558/imre.v17i3.249.

Phillips, Dana; Making Nature Sacred: Literature, Religion, and Environment in America from the Puritans to the Present; Natural Life: Thoreau's Worldly Transcendentalism. American Literature 1 September 2006; 78 (3): 648–650. doi: https://doi.org/10.1215/00029831-2006-042