Manus Lens

On the hands of fine art photography

Portraiture captures the essence of a being. In any art form, a portrait speaks to three observers: the artist, the subject, and the audience. Since the birth of photography and the classical Daguerreotypes that made portraits common household objects, individual photographers freely explored and experimented with this fundamental art genre. Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, as photography rose as an art form in society, portraiture styles changed drastically. With the formation of photographic societies such as the Linked Ring, and Photo Secession, to the widespread use of gelatin dry plates that made photography more accessible to amateurs, portraiture was given a new spotlight.

The world itself was changing during this period that spanned both the duration of World War One and the beginning of World War Two. Artistic expression shifted as the world was faced with crisis, and this response appears dramatically in portraiture style photography. The human experience was now veiled by the lingering traumas of war and the hardships following The Great Depression. Surrealism appeared, alongside Dadaism, Cubism, and Expressionism; artistic movements expanding the earlier focus on Naturalism and Pictorialism. Subjects were used in portraits for a variety of reasons, and each decision an artist made on how to portray their subject had a direct impact on the image as a whole. Bodies were replaced with faces, faces shifted into appendages, and the definition of what a portrait was became an enveloped conglomeration of one’s entire body.

The content of a portrait in its entirety is largely dependent on the eye of the artist. What is shown and what is hidden to the viewer are both decisions made on the part of the artist, whether they were conscious decisions or not. For many photographers of this era, the subjects’ hands held great significance. How the hands were positioned could change the entire feeling of an image—giving or removing the sense of life and vitality of the subject. By removing the human face, photography allowed humanity to be shown in the details of the body. Suddenly, a hand could be as mournful as downcast eyes, as expressive as a dazzling smile. In the absence of a face, and by replacing it with the human hand, the definition of portraiture evolved from the established portrait history of Rembrandt and Vermeer, and shifted the possibilities of the camera to a tool for documenting new heights of human expression.

Florence Henri, Baron Adolf de Meyer, and Alfred Stieglitz all worked portraiture into their canons of photographic work that included particular and obvious artistic decisions involving hands. Each had unique subjects, and their individual environments influenced their artistic styles. The portraiture of Baron Adolf de Meyer—a mysterious figure claiming both French and German childhood—was largely fashion oriented. Adolf de Meyer began his photographic career at a young age, and was quickly picked up by the prestigious Linked Ring society in 1899, later joining The Photo Secession. His individual style leaned more towards the Pictorialists of the era, and in 1912 he moved to the United States to join Vogue Magazine as their first full-time photographer.

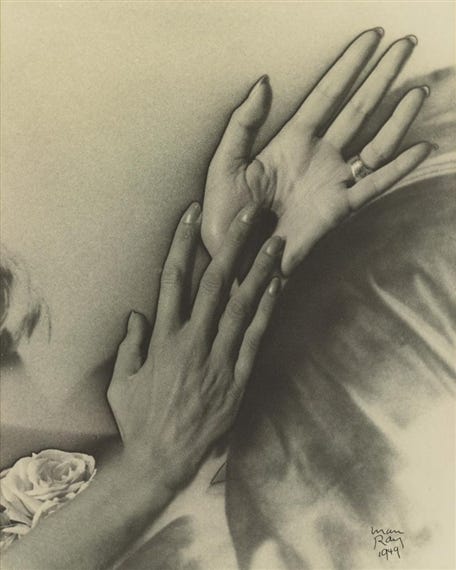

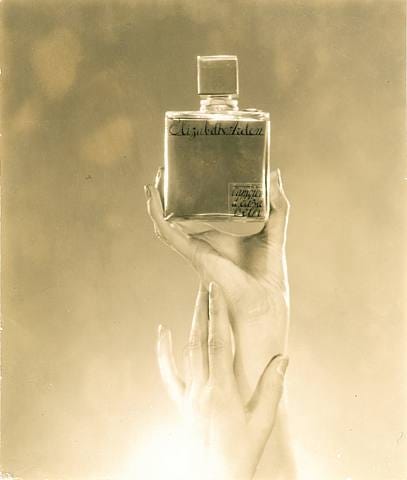

De Meyer’s fashion oriented images for Vogue had an air of magical realism, with soft focus and intricate backdrops. He utilized the photogravure process, printing his images on copper plates. In 1927, de Meyer produced a series of Elizabeth Arden advertisements that consisted of portraits highlighting the beauty that these products claimed to provide their customers with. In the Elizabeth Arden portraits, as with many of his other fashion editorials, hands play a mysterious role in the images, as they appear severed from their connecting bodies, yet alive and shimmering with prestige.

The composition of de Meyer’s images all provoked thought, with the hands of his models oftentimes clutched beneath their chins, or outstretched onto the backdrops to provide depth in the image. De Meyer turned the fashion that he photographed into more than mere advertisements, and the deliberate placement of hands added to the intrigue of his images. Faces of fashion were replaced with hands as the extension of the consumer.

Portraiture in the years spanning 1839-1940 cannot be discussed without mention of the figure at the forefront of the photographic world: Alfred Stieglitz. The artist responsible for the creation of Photo Secession and Camera Work, Stieglitz was a firm believer that photography is a medium capable of artistic expression, just as prestigious as the painting and sculpture of the time. He dedicated his professional life to defending photography as a fine art, and dabbled in many different genres of work. Stieglitz worked extensively with portraiture, and believed that a person’s personality, like the outside world, was constantly changing and could be interrupted but not halted by the intervention of the camera into the moment. In 1924 he married artist Georgia O’Keeffe. It has been said that she inspired Stieglitz to dive back into portraiture photography; rekindling the fire that had dimmed in the years since his breakthrough as an artist.

The Modernist photographers of the era who worked with portraiture believed that the entirety of their models personality should not and could not be captured within a single image, and Stieglitz himself grappled with this idea in his portraits of his wife and muse, O’Keeffe. This Modernist belief led to many of these portraits to include small portions of who O’Keeffe was as a woman. Stieglitz’s camera focused on the details that were meaningful for him, such as her hands. During their very first portrait session, Stieglitz photographed her hands, and when the images were shown to O’Keeffe, she wrote: “Nothing like that had come into our world before. The notion that an expressive portrait might be made without including the sitter’s face was indeed novel.”

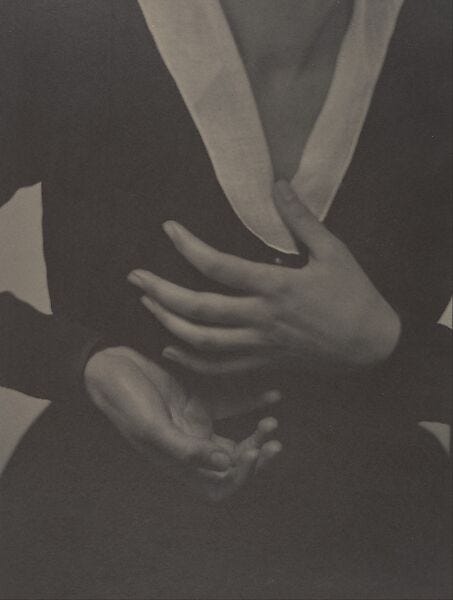

A third photographer of the time with a notable interest in hands as subjects is Florence Henri. Henri became a classically trained pianist in Rome before she began a painting career in Berlin. This eventually sparked her interest in photography as she was studying at the Bauhaus in Dessau, with her prime artistic years ranging from 1928 to 1960. Akin to the Bauhaus artists during this time, Henri’s style developed into the realm of photomontage. With multiple exposures, manipulation with mirrors, prisms, and reflective objects, she utilized the silver gelatin printing process for her negatives.

Henri eventually joined the Surrealist movement and opened her own studio. Her photographic work was dominated by portraits. Her images included many self portraits, as well as images of her close friends and artistic colleagues. She worked mostly from within her studio, and some of her most recognizable self portraits were taken there. Her surrealistic eye captured each subject in a haunting light that left the viewer contemplative on the reality of the image. Hands played an important role in her images because they represented something that was inherently human, yet with her manipulation, could appear unreal.

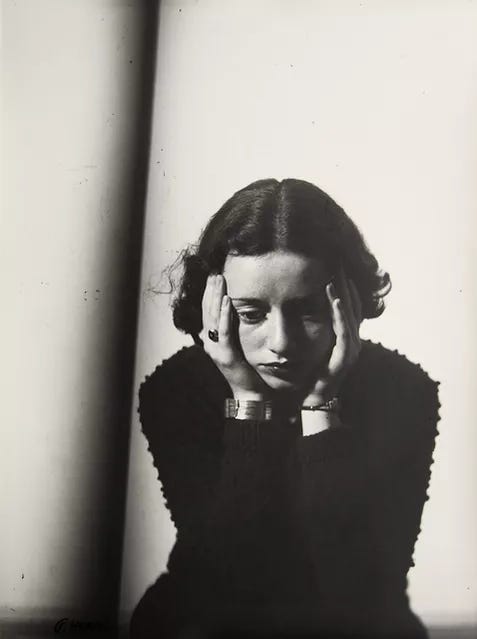

The deliberate positioning of her model's hands could represent more than just human life. Later in her career Henri taught photographic classes at her studio, and this is where she met and later photographed Lore Krüger, an aspiring photographer who began experimenting with photography near the end of the Bauhaus movement. Henri’s portrait of Krüger, taken in 1935, is a perfect example of Henri’s attention to detail, and her deliberate decision to capture Krüger in the reflective, almost overwhelmed state she is in.

Works Consulted

Hostetler, Lisa. “Adolf De Meyer.” International Center of Photography, 13 Nov. 2016, www.icp.org/browse/archive/constituents/adolf-de-meyer?all%2Fall%2Fall%2Fall%2F0.

Hostetler, Lisa. “Alfred Stieglitz (1864-1946) and American Photography.” Metmuseum.org, www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/stgp/hd_stgp.htm.

Linehan, Anna. “Florence Henri.” International Center of Photography, 2 Mar. 2016, www.icp.org/browse/archive/constituents/florence-henri?all%2Fall%2Fall%2Fall%2F0.

Martini, Giovanni Battista. “Florence Henri: Mirror of the Avant-Garde, 1927–40.” Aperture.org, 2015, aperture.org/shop/florence-henri-mirror-avant-garde-book/.

“Sex, Stieglitz and Georgia O'Keeffe: Art: Agenda.” Phaidon, www.phaidon.com/agenda/art/articles/2016/july/05/sex-stieglitz-and-georgia-o-keeffe/.

Yaeger, Lynn. “Saluting Baron Adolf De Meyer, Vogue's First Staff Photographer.” Vogue, Vogue, 1 Feb. 2017, www.vogue.com/article/adolph-de-meyer-birthday-vogue-photographer.